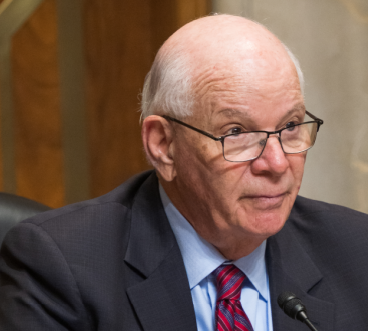

Mr. Hastings of Florida. Madam Speaker, as Chairman of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, I would like to draw the attention of my colleagues to two events last week that, taken together, illustrate the damaging effect that this administration’s policies have had on America’s credibility as a global leader on human rights, democracy and the rule of law.

First of all, on Friday, the 56 OSCE participating States concluded their annual Human Dimension Implementation Meeting in Warsaw, Poland. This meeting is Europe’s largest regional human rights forum where governments and nongovernmental organizations gather to take stock of how countries are implementing the commitments they have undertaken in the Helsinki process relating to human rights and democracy. As such, this meeting provides an important opportunity for the United States to raise and express concern about serious instances of noncompliance and negative trends in the expansive OSCE region stretching from Vancouver to Vladivostok.

Separately, on Thursday of last week–just as the Warsaw meeting was drawing to a close–the New York Times ran an article revealing the existence of two classified legal memos authorizing the use of interrogation techniques that, to many reasonable minds, rise to the level of torture, or at least cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment–both categories of treatment prohibited under the United Nations Convention Against Torture, to which the United States is a party. These memos have already been dubbed by some as “torture memo 2.0” and “torture memo 3.0,” and were reportedly authored by Steven G. Bradbury, who has headed the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel since 2005.

Madam Speaker, 3 years ago the world was shocked–and the United States was shamed–by pictures showing detainees standing on boxes with hoods over their heads and electrical wires attached to their fingers. But perhaps even more shocking and more shameful was the surfacing of the so-called “torture memo,” adopted by the Department of Justice in 2002 and leaked to the public in 2004. The very existence of such a memo was rightly and widely understood to mean that abuses did not just occur by rogue elements or as an aberration, but stemmed from a government policy to effectively authorize the use of torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. The 2002 memo was so scandalous that shortly after it was leaked, it was disavowed by the Department of Justice itself.

For many people, the existence of “torture memo 2.0” and “torture memo 3.0” will not come as a surprise but rather as a confirmation of what they suspected to be the case. Certainly, when one looks at the statements issued by the President when he signed into law the 2005 Detainee Treatment Act and the 2006 Military Commissions Act, there was every indication that he considered himself in no way bound by those laws as passed by Congress.

There are, of course, enormous implications for the United States when the President considers himself beyond the reach of the Congress and outside the scope of the Constitution. The President’s policies on torture have seriously undercut American credibility on the very issues this administration purports to hold dear–human rights and democracy promotion.

Can you imagine being at a meeting–like the one that has just concluded in Warsaw–where the United States is supposed to express its concern about a whole range of human rights issues, including the issue of protecting human rights while combating terrorism, when this latest revelation about this administration’s torture policies hits the front pages?

Regrettably, American credibility as an advocate for human rights and democracy has continued in free fall in the face of this latest revelation and attendant implausible denials. Beyond the victims of abuse themselves, U.S. interests are being seriously undermined, including the campaign to win hearts and minds around the globe. Not surprisingly, the administration’s dissembling denials cannot repair the damage that has been done. It will take considerable time to restore the good name of our country–time, and concrete action by this body,

In such circumstances, actions speak louder than words, and two steps must be taken to help restore America’s tarnished reputation, help clear out the thicket of legal cases created by the President’s disastrous policies, and position the United States to build more effective alliances in our counterterrorism operations. First, I urge my colleagues to restore habeas corpus–and the sooner, the better. The Military Commissions Act of 2006 was a travesty of justice, but perhaps no part of that legislation departed so sharply from our legal heritage as the decision to deny individuals the most basic right recognized since the Magna Carta: the right to challenge their detention. If we are to convince the world that we do not routinely torture terrorism suspects, providing these detainees one of the most basic legal safeguards is a good place to start.

Second, we must close the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay–a measure I called for at a hearing on Guantanamo I chaired in June. To this end, the United States should release or transfer detainees elsewhere and, for those whom we believe we must hold and try, detainees should be transferred to the United States. Terror suspects can be tried by our Federal courts; they might be tried by military commissions under the Uniform Code of Military Justice; I’d even consider the establishment of special domestic terror courts, as in Spain. But it is time for the President to listen to his own senior officials, including Secretaries Gates and Rice, and close the GTMO camp.

Madam Speaker, while these two steps are not the only ones necessary to fully restore America’s credibility and respect for the values we proclaim abroad, they would represent an important start. It is time for this great country to resume its rightful leadership role on human rights, democracy and rule of law, but first, it will need to lead by example.