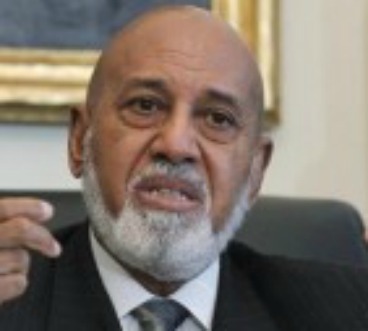

Madam Speaker, last week the Helsinki Commission, which I Chair, held a briefing at which representatives from Physicians for Human Rights presented the findings of their recently published report, “Broken Laws, Broken Lives.” In it, they documented the medical evidence of torture by U.S. personnel in 11 specific cases. I believe this briefing was the first opportunity on Capitol Hill for the public to hear specifically about the medical consequences of the administration’s detention policies and to consider some of the ethical questions related to the medical treatment of detainees, including forced feeding and the possible role of medical professionals during interrogations.

We were fortunate to have with us as panelists Leonard Rubenstein, J.D., President of Physicians for Human Rights; Dr. Allen Keller, Advisor to Physicians for Human Rights and Director of the Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture; and Dr. Scott Allen, also an Advisor to Physicians for Human Rights.

For many years, members of the Helsinki Commission have been actively engaged on issues related to torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment or punishment. Over the years, we have raised concern about the nearly constant reports of torture and abuse in Chechnya. We have pressed Turkey to provide detainees with prompt access to lawyers and medical personnel, because we know that when people are held incommunicado, they are more likely to experience torture. We have expressed alarm regarding the number of people who walk into Uzbekistan jails on their own two feet–and who have been returned to their families in boxes.

Last week, it was my sad duty to hear representatives from Physicians for Human Rights describe the torture and ill-treatment some detainees have experienced at the hands of U.S. personnel. As I noted then, I certainly expected to hear about the medical and psychological impact of this torture on the individuals whose cases were investigated by Physicians for Human Rights. But, coincidently, there was a different kind of impact on display last week, when the U.S. also opened its first war crimes trial since World War II.

In the trial of Salim Hamdan, alleged to be Osama bin Laden’s driver, the military judge overseeing the case found it necessary to exclude from evidence several statements of the defendant because they were obtained under what the military judge deemed “highly coercive” conditions. Another one of the government’s efforts to bring a defendant before a military tribunal had already been put indefinitely on hold, reportedly because the evidence in the case cannot be disentangled from the impermissible methods that were used to extract it. In other words, the use of abusive interrogation methods has undermined the government’s ability to prosecute people suspected of terrorism or terrorism-related crimes.

Let me repeat: the ill-conceived policy of “enhanced interrogations” has undermined our country’s ability to prosecute people for the most serious crimes committed against this nation.

As it happened, on the day of our briefing last week, the ACLU released three new “torture memos” it had obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. Although highly redacted–indeed, one of them has ten pages that are entirely blacked out–these documents nevertheless provide some additional insight into the development of the policies that set the stage for what Major General Antonio Taguba, in his preface for the Physicians for Human Rights report, called “a systematic regime of torture.” (You may recall that General Taguba led the U.S. Army’s official investigations into the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal.)

Here’s just one bit of information we now have from a memo prepared by the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel on August 1, 2002 and released last week. This memo, prepared for the CIA, advises that the crime of torture, as defined by U.S. statute, requires a showing of specific intent to cause severe pain or suffering. That specific intent, in turn, will be negated if a defendant acts with a good faith belief that his actions will not cause severe pain or suffering. That good faith belief can be demonstrated by showing that an official acted in reliance on the advice of experts. And guess what? The Office of Legal Counsel is a bunch of experts. And they go on to say that the objective of the interrogation techniques under discussion–we don’t know precisely what they are because they’re blacked out–is not to cause severe physical pain. Just like magic, you have your expert advice, which gives you your good-faith belief, which negates the specific intent required under the statute which criminalizes torture. So you guys can go ahead and waterboard and God knows what else because the Office of Legal Counsel has told you that it does not cause severe pain or suffering, so you have legal license to ignore your own eyes and ears, which tell you that waterboarding will break a person in minutes.

Madam Speaker, the report by Physicians for Human Rights makes several recommendations that deserve study and consideration. But in light of the release of these most recent torture memos, I would like to highlight today one particular recommendation of the report: “The U.S. Department of Justice should publicly release all legal opinions and other memoranda concerning standards regarding interrogation and detention policy and practices.”

The Department of Justice is the arbiter of what is the law of the land for this country. And I think the American people have a right to know if their government has sought to redefine “torture” as “not torture.” Accordingly, I urge the Attorney General to release the full texts of all the memos relating to interrogation and detention policies and practices.