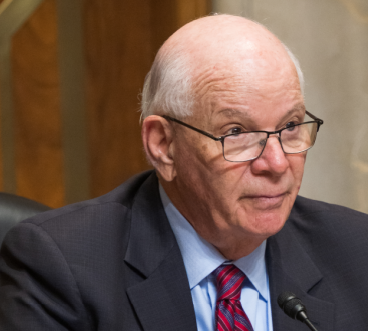

COLLEGE PARK, MARYLAND – Today at the University of Maryland at College Park, Senator Benjamin L. Cardin (D-MD), Co-Chairman of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (U.S. Helsinki Commission), chaired a field hearing examining torture and other forms of banned treatment, with Commission Chairman Congressman Alcee L. Hastings (D-FL). The hearing entitled, “Is it torture yet?” focused on what constitutes torture or other forms of prohibited ill-treatment, what legal norms apply, and what is known about the effectiveness of various interrogation methods.

Expert testimony was received from Ms. Devon Chaffee, Associate Attorney, Human Rights First; Dr. Thomas C. Hilde, School of Public Policy, University of Maryland-College Park; Dr. Christian Davenport, Professor of Political Science, University of Maryland-College Park, and Senior Fellow and Director of Research at the Center for International Development and Conflict Management; and Mr. Malcom Nance, Director, Special Readiness Services International and Director, International Anti-Terrorism Center for Excellence.

During the hearing, both Senator Cardin and Congressman Hastings were critical of United States policy on torture and expressed their concerns over the destruction of CIA videotapes of terror suspects under interrogation. It was also noted that today is International Human Rights Day, a day which commemorates the adoption of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights nearly 60 years ago.

“I deeply regret that, six decades after the adoption of the Universal Declaration, it is necessary to have a hearing on torture and, more to the point, I regret that the United States’ own policies and practices must be a focus of our consideration,” said Senator Cardin. Congressman Hastings also noted: “I am profoundly frustrated by the damage that has been done to America’s good name and credibility by the documented instances of abuse that have occurred in the context of our country’s effort to combat terrorism, and by the erosion of the legal principles which make torture and other forms of ill-treatment a crime.”

Full opening statements from the hearing are below:

Co-Chairman Cardin’s Statement:

“Mr. Chairman, I am happy to conduct this hearing today, examining some of the complex legal and policy questions relating to torture, and very grateful to the University of Maryland for providing us with the outstanding facilities to hold this field hearing.

“As it happens, today is International Human Rights Day, a day which commemorates the adoption of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights nearly 60 years ago. As stated in that historic document: “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”’

“Since then, the United States has adopted other international commitments and obligations relating to humane treatment: the 1949 Geneva Conventions, the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and, of course, the 1984 Convention Against Torture.

“In the Helsinki process, the United States has joined with the 55 other participating States to condemn torture. A compilation of those OSCE commitments is available on the table outside this room, but I want to quote one particular provision, because it speaks with such singular clarity. In 1989, in the Vienna Concluding Document, the United States – along with the Soviet Union and all the other participating States – agreed to “ensure that all individuals in detention or incarceration will be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person.” There are no exceptions or no loopholes, and this is the standard which the United States is obligated to uphold.

“I deeply regret that, six decades after the adoption of the Universal Declaration, it is necessary to have a hearing on torture and, more to the point, I regret that the United States’ own policies and practices must be a focus of our consideration.

“As a member of the Helsinki Commission, I have long been concerned about the persistence of torture and other forms of abuse in the OSCE region. I am particularly troubled by the pattern of torture in Uzbekistan — a country to which the United States has extradited terror suspects. In November alone, Radio Free Europe reported that two individuals died while in the custody of the state. Their bodies, when returned to their families, bore all the markings of torture.

“Unfortunately, United States leadership in the effort to combat torture and other forms of ill-treatment has been undermined by the revelation of abuse at Abu Ghraib and elsewhere. In fact, when Secretary of State Rice met with leading human rights activists in Moscow in October, they told her that allegations of abuse at the U.S.-run Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq have hurt Washington’s authority on human rights.

“As horrific as the revelations of abuse at Abu Ghraib were, in a certain respect the government’s own legal memos on torture may be even more damaging, since they appear to reflect a policy to condone torture and immunize those who may have committed torture.

“Torture remains a serious problem in a number of OSCE countries, particularly in the Russian region of Chechnya, but if the United States is to address those issues credibly, we must get our own house in order.

“In this regard, I was deeply disappointed by the unwillingness of Attorney General Mukasey to state clearly and unequivocally that waterboarding is torture. As a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, I chaired part of the Attorney General’s confirmation hearing. And I found his responses to questions relating to torture woefully inadequate. As it happens, on November 14, I also participated in another Judiciary Committee hearing at which an El Salvadoran torture survivor testified. This medical doctor, who can no longer practice surgery because of the torture inflicted upon him, wanted to make one thing very clear: as someone who had been the victim of what his torturers called “the bucket treatment,” he said, waterboarding is torture.

“Earlier this year, former Bush administration counselor Phillip Zelikow argued that, whether legal or not, the interrogation policies developed in 2002 were just flat-out “immoral.” (Specifically, he said, “My own view is that the cool, carefully considered, methodical, prolonged, and repeated subjection of captives to physical torment, and the accompanying psychological terror, is immoral. I offer no opinion as to whether such conduct is a federal crime; merely that it is immoral.”) He added: “Sliding into habits of growing non-cooperation and alienation is not just a problem of world opinion. It will eventually interfere – and interfere very concretely – with the conduct of worldwide operations.”’

“At today’s hearing, we will certainly consider the laws that govern torture and other forms of ill-treatment – and on that score, we may hear views that differ from Mr. Zelikow’s. But our witnesses will expand this discussion to the moral and ethical issues that Zelikow argued should have been considered by the administration – and were not. I believe our witnesses may also pose some provocative questions about the relationship between human rights violations and democracy,” said Cardin.

Chairman Hastings’ statement:

“Senator Cardin, I want to thank you for your leadership in convening this field hearing and I’d also like to express my appreciation to President Mote and the University of Maryland for their hospitality today.

“This hearing comes just days after the revelation that two videotapes made in 2002, showing the CIA’s interrogation of two terror suspects, were destroyed by the Central Intelligence Agency in 2005. One can only wonder what those videos showed.

“The destruction of these tapes is disturbing on many levels, but especially when one considers that the 9/11 Commission specifically and formally sought these sorts of recordings and were not given them. I cannot imagine why, when the 9/11 Commission was investigating one of the worst attacks on American soil in the history of our country, why the CIA did not fully cooperate with that investigation.

“Like you, Senator Cardin, I am profoundly frustrated by the damage that has been done to America’s good name and credibility by the documented instances of abuse that have occurred in the context of our country’s effort to combat terrorism, and by the erosion of the legal principles which make torture and other forms of ill-treatment a crime.

“Many people have said it, but it seems to me to deserve repeating, and I put this in the context as someone who has visited more intelligence stations than probably any other current Member of Congress: Torture does not make us any safer. Torture does not produce good intelligence.

“In fact, there have been several notorious instances of detainees providing testimony under duress that has subsequently been shown to be false. Some of the evidence relied upon by Secretary Powell, in his 2003 speech to the UN making the case for the war in Iraq, came from a detainee who later recanted that testimony and stated that he made his claims as a result of coercive interrogation. Three British detainees at Guantanamo confessed to being at an Al Qaeda training camp, but British authorities later confirmed that all three of the men were in the United Kingdom at the time they told their American interrogators they were meeting with Osama bin Laden. Those men have all been released now.

“As we examine the subject of torture today, I look forward to hearing our witnesses discuss various aspect of this issue. But I also hope that the administration will begin to devote some serious attention and resources to study better ways to gain intelligence. Too often intelligence gathering and respect for human rights are presented as a zero-sum game, where more of one means less of another. I think that is a false paradigm. There is more we can be doing to improve our intelligence gathering that does not have to come at the expense of human rights – for example, we could stop kicking people out of the military who have critically needed foreign language skills just because they’re gay. We can provide more training for critical languages. We can study non-coercive interrogation methods – something we haven’t done since World War II. None of those things involve or require torture.

“Finally, Senator Cardin, I would like to express my immense disappointment – to say the least – to hear that President Bush is prepared to veto the 2008 Fiscal Year intelligence authorization bill because it would require the Central Intelligence Agency to follow the same interrogation norms that apply to military personnel. As it now stands, the 2006 Detainee Treatment Act prohibits military personnel from engaging in torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment of detainees.

“Last February, Jeffrey H. Smith, the former General Counsel to the CIA, argued strongly in the pages of the Washington Post that armed services and the CIA should not have different standards for the treatment and interrogation of detainees – and I think he’s right. So I truly hope that the intelligence authorization bill will be passed, including its provision regarding CIA interrogations norms, and I hope that the President will expeditiously sign it into law.

“Senator, thank you again for your thoughtful and long-standing leadership on this issue. I am proud to be with you today at your state’s flagship university to explore how this issue impacts the United States– both right here at home and across the globe. Thank you,” said Hastings.