Mr. Speaker, I rise today to bring to the attention of my colleagues disturbing news about the presidential elections in Kazakhstan last month, and the general prospects for democratization in that country. On January 10, 1999, Kazakhstan held presidential elections, almost two years ahead of schedule. Incumbent President Nursultan Nazarbaev ran against three contenders, in the country’s first nominally contested election. According to official results, Nazarbaev retained his office, garnering 81.7 percent of the vote. Communist Party leader Serokbolsyn Abdildin won 12 percent, Gani Kasymov 4.7 percent and Engels Gabbasov 0.7 percent. The Central Election Commission reported that over 86 percent of eligible voters turned out to cast ballots. Behind these facts, and by the way, none of the officially announced figures should be taken at face value, is a sobering story.

Nazarbaev’s victory was no surprise: the entire election was carefully orchestrated and the only real issue was whether his official vote tally would be in the 90s, typical for post-Soviet Central Asian dictatorships, or the 80s, which would have signaled a bit of sensitivity to Western and OSCE sensibilities. Any suspense the election might have offered vanished when the Supreme Court upheld a lower court ruling barring the candidacy of Nazarbaev’s sole plausible challenger, former Prime Minister Akezhan Kazhegeldin, on whom many opposition activists have focused their hopes. The formal reason for his exclusion was both trivial and symptomatic: in October, Kazhegeldin had spoken at a meeting of an unregistered organization called “For Free Elections.” Addressing an unregistered organization is illegal in Kazakhstan, and a presidential decree of May 1998 stipulated that individuals convicted of any crime or fined for administrative transgressions could not run for office for a year. Of course, the snap election and the presidential decree deprived any real or potential challengers of the opportunity to organize a campaign.

More important, most observers saw the decision as an indication of Nazarbaev’s concerns about Kazakhstan’s economic decline and fears of running for reelection in 2000, when the situation will presumably be even much worse. Another reason to hold elections now was anxiety about the uncertainties in Russia, where a new president, with whom Nazarbaev does not have long-established relations, will be elected in 2000 and may adopt a more aggressive attitude towards Kazakhstan than Boris Yeltsin has.

The exclusion of would-be candidates, along with the snap nature of the election, intimidation of voters, the ongoing attack on independent media and restrictions on freedom of assembly, moved the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) to call in December for the election’s postponement, as conditions for holding free and fair elections did not exist. Ultimately, ODIHR refused to send a full-fledged observer delegation, as it generally does, to monitor an election. Instead, ODIHR dispatched to Kazakhstan a small mission to follow and report on the process. The mission’s assessment concluded that Kazakhstan’s “election process fell far short of the standards to which the Republic of Kazakhstan has committed itself as an OSCE participating State.” That is an unusually strong statement for ODIHR.

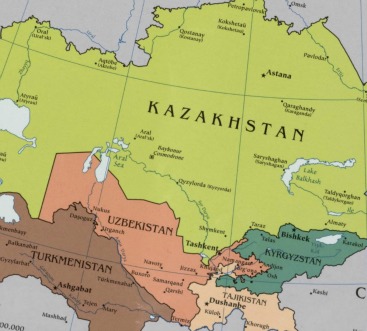

Until the mid-1990s, even though President Nazarbaev dissolved two parliaments, tailored constitutions to his liking and was single-mindedly accumulating power, Kazakhstan still seemed a relatively reformist country, where various political parties could function and the media enjoyed some freedom. Moreover, considering the even more authoritarian regimes of Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan and the war and chaos in Tajikistan, Kazakhstan benefited by comparison. In the last few years, however, the nature of Nazarbaev’s regime has become ever more apparent. He has over the last decade concentrated all power in his hands, subordinating to himself all other branches and institutions of government. His apparent determination to remain in office indefinitely, which could have been inferred by his actions, became explicit during the campaign, when he told a crowd, “I would like to remain your president for the rest of my life.” Not coincidentally, a constitutional amendment passed in early October conveniently removed the age limit of 65 years. Moreover, since 1996-97, Kazakhstan’s authorities have co-opted, bought or crushed any independent media, effectively restoring censorship in the country. A crackdown on political parties and movements has accompanied the assault on the media, bringing Kazakhstan’s overall level of repression closer to that of Uzbekistan and severely damaging Nazarbaev’s reputation.

Despite significant U.S. strategic and economic interests in Kazakhstan, especially oil and pipeline issues, the State Department has issued a series of critical statements since the announcement last October of pre-term elections. These statements have not had any apparent effect. In fact, on November 23, Vice President Gore called President Nazarbaev to voice U.S. concerns about the election. Nazarbaev responded the next day, when the Supreme Court, which he controls completely, finally excluded Kazhegeldin. On January 12, the State Department echoed the ODIHR’s harsh assessment of the election, adding that it had “cast a shadow on bilateral relations.”

What’s ahead? Probably more of the same. Parliamentary elections are slated for October 1999, although there are indications that they, too, may be held before schedule or put off another year. A new political party is emerging, which presumably will be President Nazarbaev’s vehicle for controlling the legislature and monopolizing the political process. The Ministry of Justice on February 3 effectively turned down the request for registration by the Republican People’s Party, headed by Akezhan Kazhegeldin, signaling Nazarbaev’s resolve to bar his rival from legal political activity in Kazakhstan. Other opposition parties which have applied for registration have not received any response from the Ministry.

Mr. Speaker, the relative liberalism in Kazakhstan had induced Central Asia watchers to hope that Uzbek- and Turkmen-style repression was not inevitable for all countries in the region. Alas, all the trends in Kazakhstan point the other way: Nursultan Nazarbaev is heading in the direction of his dictatorial counterparts in Tashkent and Ashgabat. He is clearly resolved to be president for life, to prevent any institutions or individuals from challenging his grip on power and to make sure that the trappings of democracy he has permitted remain just that. The Helsinki Commission, which I co-chair, plans to hold hearings on the situation in Kazakhstan and Central Asia to discuss what options the United States has to convey the Congress’s disappointment and to encourage developments in Kazakhstan and the region towards genuine democratization.