Rayburn House Office Building, Room 2247

Stream live here

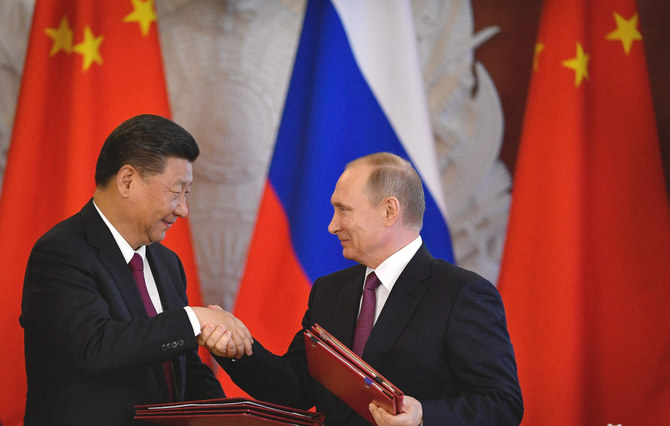

While U.S. allies in Europe have spent the past several years prioritizing responding to Russia’s aggression, they have allowed another authoritarian power to take hold in key economic sectors, public institutions, and research fields. For China, sustaining Russia’s war on Ukraine is one piece of a broader campaign to weaken and mold Europe to its vision. To do so, China relies on a variety of approaches, ranging from covert political influence to predatory industrial policy to transnational repression, tailoring its approach to each country and institution it targets.

Allowing China, aided by a belligerent Russia, to capitalize on seams in the transatlantic relationship and assert itself in Europe threatens both U.S. strategic interests and the NATO alliance. And yet, many on the continent are only slowly recognizing that Chinese interest and investment must be met with caution, as it often comes with downsides for national security, sovereignty, and rule of law. Countries that experienced Russian occupation are most attuned to the risks of allowing another authoritarian power into their midst and can serve as a model for Europe in implementing policies that protect Europeans from the complications of Chinese investment and influence.

This hearing will assess China’s growing access to key sectors, governments, and institutions throughout Europe, and U.S. strategic interests in interrupting this trend. Witnesses will discuss the role the United States can play to support our allies in hardening their systems against the threats China poses to collective security and creating a more unified global deterrent to China and its authoritarian partners.

Witnesses:

Vidmantas Verbickas, Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lithuania

Audrye Wong, nonresident senior fellow, American Enterprise Institute

Valbona Zeneli, nonresident senior fellow, the Atlantic Council

###