On February 5, 2018, President Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan announced that the country’s presidential elections—originally scheduled for the fall—instead would be moved forward to April 11, 2018.

While some pro-government commentators offered more innocuous explanations for the move—such as aiming to avoid simultaneous presidential and parliamentary elections in 2025—many independent analysts saw it as a ploy to disadvantage the opposition. Since Azerbaijani law requires campaigning to cease 30 days prior to the vote, candidates had very little time to rally support. This constraint, among others, contributed to the mainstream opposition boycott of the election.

The vote was the first since Azerbaijan passed constitutional amendments in a widely criticized popular referendum in September 2016 that extended the president’s term from five to seven years. Having done away with term limits in another set of constitutional amendments in 2009, President Aliyev used the snap election to secure his position until 2025. The official tally gave Aliyev 86 percent of the vote—he has never won with less than 84 percent.

Since signing the founding document of the OSCE, the Helsinki Final Act, in 1992, no national vote in Azerbaijan has met the OSCE’s minimum requirements for a free and fair election. Nevertheless, consistent with its commitments as an OSCE participating State, Azerbaijan invited international observers to view the election. The OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly (OSCE PA) and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) all scrambled to assemble a robust Election Observation Mission (EOM) in Azerbaijan under difficult time constraints.

Two U.S. Helsinki Commission staff members joined the OSCE PA EOM. The article below summarizes their experience in Azerbaijan.

By Scott Rauland, Senior State Department Advisor

and Jordan Warlick, Office Director

Briefings Reveal Shortcomings in the Field of Candidates and Lack of Media Access

From the beginning, it was clear that the Government of Azerbaijan was paying lip service to established OSCE norms for holding elections without providing voters with the necessary conditions to make an informed choice free of coercion.

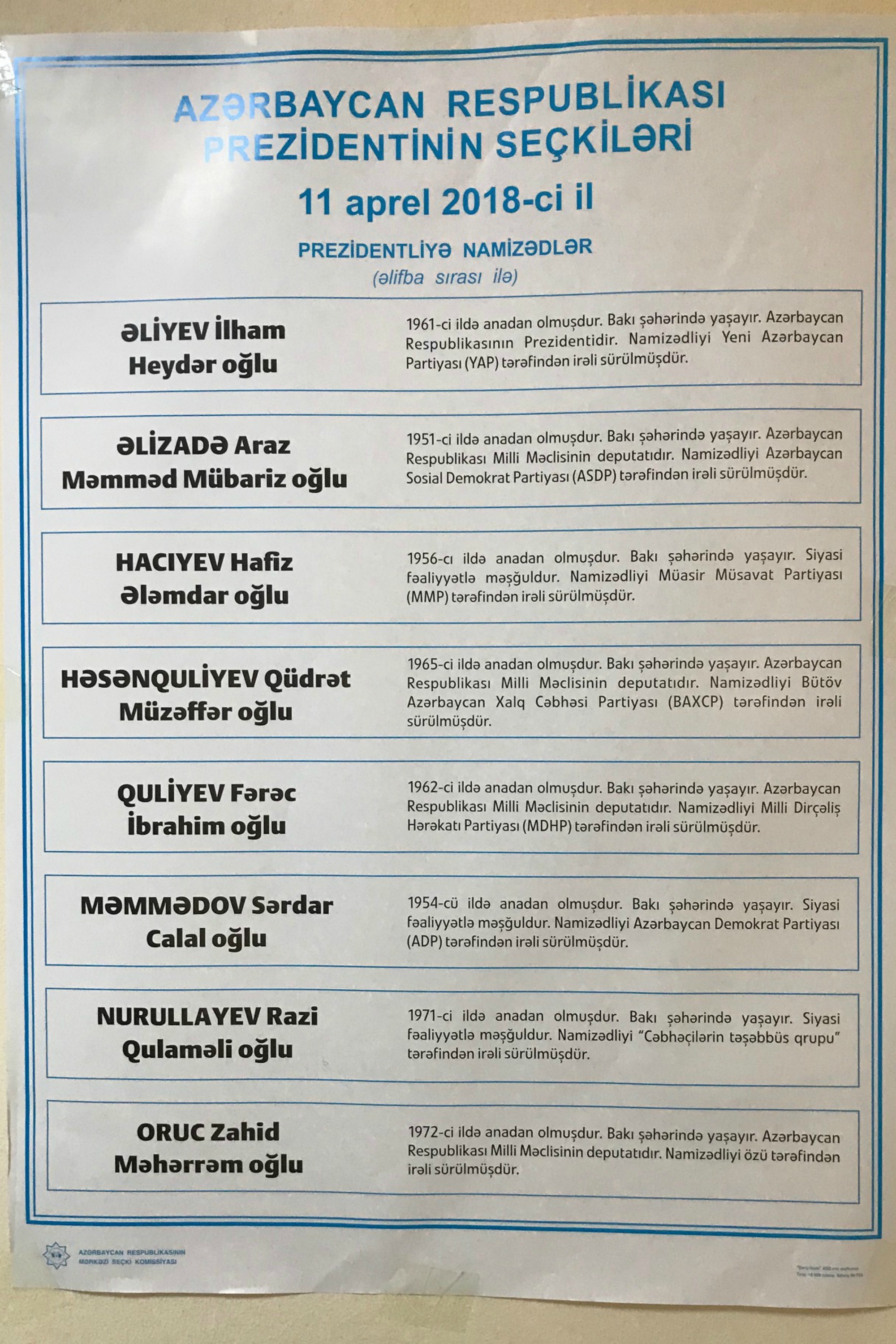

For example, prior to the vote, we and other short-term members of the OSCE PA and PACE observation missions met with representatives of the eight candidates who had been approved by Azerbaijan’s Central Election Commission to run in the April 11 contest. During the 20-minute sessions with the candidates or their representatives, we heard almost nothing in the way of criticism of the sitting president, nor anything resembling a platform for running the country should they win.

During briefings the following day, members of opposition parties, as well as representatives of civil society and the media, pointed out the gulf of approximately 1.9 million Azerbaijanis entered on voter registration lists (5.3 million), and the number of Azerbaijanis known to be of voting age (7.2 million). Since voter registration is automatic—and all citizens who are 18 years of age by election day have the right to vote—his dramatic shortfall appeared to reflect the disenfranchisement of an astonishingly large number of Azerbaijani voters. In a separate briefing earlier, the Central Election Commission of Azerbaijan addressed this concern by claiming that the voter registration lists were published on the Internet, providing a maximum level of transparency.

During briefings the following day, members of opposition parties, as well as representatives of civil society and the media, pointed out the gulf of approximately 1.9 million Azerbaijanis entered on voter registration lists (5.3 million), and the number of Azerbaijanis known to be of voting age (7.2 million). Since voter registration is automatic—and all citizens who are 18 years of age by election day have the right to vote—his dramatic shortfall appeared to reflect the disenfranchisement of an astonishingly large number of Azerbaijani voters. In a separate briefing earlier, the Central Election Commission of Azerbaijan addressed this concern by claiming that the voter registration lists were published on the Internet, providing a maximum level of transparency.

Civil society representatives were unanimous in their view that none of the “opposition” candidates running were real candidates. The best opposition leaders had either been imprisoned or were otherwise prevented from running, they explained.

Several parties that civil society groups considered to be legitimate were boycotting the elections. Among the reasons they offered for the boycott was the fact that there were no real opposition parties in Parliament, no media freedom in Azerbaijan, and many political prisoners.

One opposition group, the Musavat Party, claimed that “clone” parties—such as the “Modern” Musavat Party, headed by Hafiz Hajiyev—had been set up to mimic true opposition parties. Hajiyev seemed to confirm those suspicions on election day by revealing that he himself had voted for President Aliyev. He also reportedly expressed his hope that President Aliyev would return the favor by appointing him prime minister.

Both civil society groups and political parties raised concerns about the potential for election fraud, due to the dramatic increase in use of de-registration voter cards (DVCs), which allow a voter to come off the voter roll in one polling station and to vote in another. We were told that while only 30,000 DVCs had been used in the previous election, 150,000 had been printed for the election on April 11. The discrepancy left many suspicious that DVCs could be abused by allowing voters to vote multiple times in different polling stations.

Civil society representatives also were concerned about voter access to information, noting that restrictive laws and lack of funding made it nearly impossible to educate voters about their choices. They also found the lack of election commission reform frustrating, pointing out that both the European Court of Human Rights and the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission provided explicit recommendations to the Azerbaijani government following previous elections. Finally, they stated that the government’s claim that 50,000 people had been registered as observers was misleading, since many of the registered observers were state employees and could not be fair and impartial observers.

A journalist briefing the observers also drew attention to the 10 Azerbaijani journalists currently in prison, saying that the regime had “made telling the truth in Azerbaijan illegal.”

Voting on April 11—Mostly by the Book

On election day, 350 international observers deployed across the country. Our team was assigned to the Khatai district in eastern Baku. We watched the opening of one polling station at 7:00 a.m., observed voting in 14 different polling stations throughout the day, and witnessed the counting process at another precinct once the polls closed at 7:00 p.m.

On election day, 350 international observers deployed across the country. Our team was assigned to the Khatai district in eastern Baku. We watched the opening of one polling station at 7:00 a.m., observed voting in 14 different polling stations throughout the day, and witnessed the counting process at another precinct once the polls closed at 7:00 p.m.

The Precinct Electoral Commissions (PECs) at all 16 locations were cooperative, and we could move freely around the polling stations to observe the entirety of the voting process. The chairwoman of the PEC where we observed the opening was willing to answer every question we had, often going into great detail.

While we were unrestricted in our ability to access polling sites, the spots in the polling stations reserved for observers were often poorly situated, being either in a corner out of direct sight of the registration tables, or in one case on another floor entirely.

One irregularity we consistently observed related to guaranteeing that each voter cast only one vote. Voters were supposed to have their left thumb coated in invisible ink once they were processed to vote, and all voters were to have their left thumbs checked before entering a polling station to ensure they had not voted elsewhere. One of the many problems with this method became obvious at the first polling station we visited, where the person checking voters’ thumbs was scanning the wrong hand.

Fellow OSCE PA observers noted that some voters showed up at the wrong polling station, where they had their thumbs sprayed in invisible ink. Once they were directed to the correct voting station, they were allowed to vote regardless of the invisible ink on their hands.

Citizen “Observers” in Name Only

During a pre-election briefing, the chair of the Central Electoral Commission proudly claimed that 57,313 Azerbaijanis had been registered as citizen observers—a large number in a country of only 9.7 million. The statistic presumably was intended to demonstrate that the elections would be both transparent and credible.

We soon noticed that few, if any, of these citizen observers paid attention to the voting. At almost every polling station, we found one or more observers who could not tell us what party they were representing. They often had to check their observer ID cards to before replying; when we then asked them which candidate from that party was running for president—information not available on their observer IDs—many were stumped.

The Polls Close—Let the Counting … and the Shenanigans … Begin

While the polls were open, election regulations appeared to be broadly respected. However, at the precinct where we observed the counting process, vote tallies were rushed and established procedures were not followed.

For example, voter registration lists were not checked to determine how many people voted in that location—a figure that should have been compared to the number of ballots in the ballot box. Unused ballots were counted and destroyed according to the established procedure, but none of this information was entered onto the protocol, the written record of votes that is supposed to be maintained throughout the vote-counting process.

For example, voter registration lists were not checked to determine how many people voted in that location—a figure that should have been compared to the number of ballots in the ballot box. Unused ballots were counted and destroyed according to the established procedure, but none of this information was entered onto the protocol, the written record of votes that is supposed to be maintained throughout the vote-counting process.

Instead, poll workers opened the ballot boxes almost immediately after the unused ballots were destroyed. The ballots then were dumped onto a table in the middle of the room and quickly sorted into several piles.

We were allowed to approach and circle the table, and had good views of the ballots on every part of the table. Most—easily 80 percent to 90 percent of the ballots—ended up in one of several piles for President Aliyev. Of the non-Aliyev piles, the largest was for ballots which appeared to be spoiled.

One member of the PEC explained to us that although some ballots had several names marked, they would not necessarily be considered spoiled; instead, they would be discussed later. Unfortunately, to the best of our knowledge, that discussion never took place.

In just over an hour, the protocol was hastily composed and finalized. Under Azerbaijani law, copies should be made available to bona fide observers; however, election officials declined to provide us with a copy. We then asked if we could at least take a photo of the protocol, and were told that the precinct would have to obtain permission from higher authorities.

We were not the only international observers who noted problems with the counting process. About 50 percent of OSCE PA observers determined that the count was either “bad” or “very bad,” well above the OSCE norm of 17 percent.

Election Aftermath

In a press conference in Baku the day after the election, observers from the OSCE/ODIHR, OSCE PA, and the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly announced that the presidential election in Azerbaijan took place “within a restrictive political environment and under laws that curtail fundamental rights and freedoms, which are prerequisites for genuine democratic elections.”

“Against this backdrop and in the absence of pluralism, including in the media, the election lacked genuine competition,” they said.

The preliminary statement from the three groups noted that other candidates refrained from directly challenging or criticizing the incumbent, and that no distinction was made between his campaign and his official activities. Observers reported widespread disregard for mandatory procedures, a lack of transparency, and numerous serious irregularities, including ballot box stuffing. More than half of the vote counts were assessed negatively, largely due to deliberate falsifications and an obvious disregard for procedures.

At the same time, observers noted that the authorities were cooperative and international observers were able to operate freely in the pre-election period, and the election administration was well resourced and prepared the election efficiently.

Announcing the conclusions, Portuguese parliamentarian Nilza de Sena said, “We have noted the positive attitude displayed by the national authorities of Azerbaijan towards international election observation, as well as the professional work of the Central Election Commission in the pre-election period. We stand ready to continue our co-operation and turn it into a joint effort to tackle the fundamental problems that a restrictive political and legal environment, which does not allow for genuine competition, poses for free elections.”

The beginning of de Sena’s statement was interrupted by a pro-government journalist who surged threateningly towards the speakers, shouting angrily that the report had been prepared in advance and that its findings were all lies. It was clear that the pro-government journalist intended on disrupting the conference to distract from the content of the findings. The press conference was suspended until the atmosphere calmed and the representatives from ODIHR, OSCE PA, and PACE could deliver their statement.

“A few weeks of campaigning during which candidates could present their views on television cannot make up for years during which restrictions on freedom of expression have stifled political debate,” said Margareta Kiener Nellen, Head of the Swiss delegation to the OSCE PA who led the 48-member OSCE PA delegation. “The OSCE Parliamentary Assembly will certainly continue to support all steps by the authorities that will bring the country forward on a path towards creating the open political environment necessary for truly free and fair elections.”