By Annie Lentz,

Max Kampelman Fellow

On August 1, 1975, after years of negotiation and debate, the leaders of 35 nations gathered in Helsinki, Finland to sign the Helsinki Final Act, also known as the Helsinki Accords. The Helsinki Final Act—the founding document of today’s OSCE—is not a treaty, but rather an international agreement outlining 10 guiding principles for inter-state relations, among them respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.

The Helsinki Final Act marked the first time that the Soviet Union had signed a transnational agreement that included language on protecting human rights. With the passage of the act came a wave of hope that renewed value would be placed on human rights and freedom in the signatory countries.

However, U.S. public opinion was not behind the Helsinki Final Act. Public understanding of the document was mired in misperceptions, and the agreement remained controversial even after it was signed by President Gerald Ford.

While the Helsinki Final Act was eventually met with hard-won respect in the U.S.—including that of Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who was originally skeptical of its utility—not all signatory countries adhered. The biggest transgressor was the Soviet Union, which jailed its citizens, restricted them from leaving the country, and limited their freedoms, all in direct violation of the Helsinki Final Act.

Some in Congress began looking for ways to hold the Soviet Union accountable for its actions. The Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (also known as the Helsinki Commission)—the brainchild of the courageous and tenacious Rep. Millicent Fenwick—was the result.

Rep. Millicent Fenwick

Millicent Fenwick was born in New York City on February 25, 1910. Raised in New Jersey, she became involved with politics in the 1950s through the civil rights movement. Finding her footing in New Jersey politics, Fenwick ran and won a seat in the New Jersey Assembly, ultimately becoming elected to Congress as a representative for New Jersey in 1974. She was 64 years old.

Appalled by the Russian neglect of the Helsinki Final Act and the theft of freedom from its citizens, the newly elected Rep. Fenwick projected a resounding voice on the topic of human rights advocacy and accordance to the Helsinki Final Act.

Rep. Fenwick’s activism was prompted by a 1975 visit to Russia, one week after the Helsinki Final Act was signed. As noted in Amy Shapiro’s book, Millicent Fenwick: Her Way, the visit brought on a revelation.

“You read about an automobile accident and you’re shocked,” Rep. Fenwick said. “But you come upon that accident and see the blood on the victims and hear their cries – how different it is. Well, that’s what it was like to go to Russia and hear the cries of all these desperate people.”

Specifically, Rep. Fenwick empathized with the case of Lelia Ruitburd, whose husband and son were arrested by the police at the Yalta Airport for conspiring to emigrate.

While Ruitburd’s son was eventually released, her husband disappeared forever. Ruitburd lived the remainder of her life worried, anxious, and utterly alone, all because her family had hoped for a better life outside of the Iron Curtain.

Witnessing such devastation first-hand, Rep. Fenwick leapt into action, becoming one of the two primary advocates for the creation of a U.S. body to observe and promote compliance with the human rights provisions of the Helsinki Final Act, alongside Sen. Clifford Case, also of New Jersey.

Establishment of the Helsinki Commission

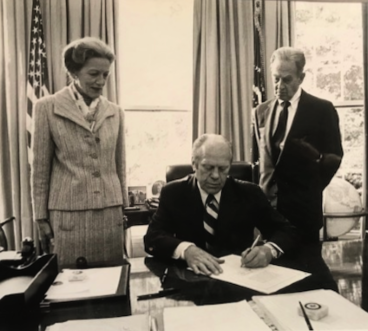

Rep. Millicent Fenwick, President Gerald Ford, and

Senator Clifford Case at the signing of Public Law 94-304.

Rep. Fenwick’s advocacy manifested in Public Law 94-304 of June 3, 1976, the legislation that created the Helsinki Commission. Her partnership with Senator Case was instrumental in passing the law.

The new law authorized the Helsinki Commission “to monitor the acts of the signatories which reflect compliance with or violation of the articles of the Final Act…with particular regard to the provisions relating to human rights and Cooperation in Humanitarian Fields.” This mandate extended to other areas covered by the Helsinki Final Act, including economic cooperation and the exchange of people and ideas between participating States.

The primary goals of the commission were to strengthen the legitimacy of human rights monitoring; to defend those persecuted for acting on their rights and freedoms; to ensure that violations of Helsinki provisions were given full consideration in U.S. foreign policy; and to gain international acceptance of human rights violations as a legitimate subject for one country to raise with another.

Backlash for Oversight

Within the U.S. the establishment of the Commission was controversial. Public Law 94-304 was signed against the advice of senior foreign policy advisors, including Secretary of State Kissinger. As noted in Shapiro’s book, Kissinger “preferred bilateral negotiations between Washington and Moscow rather than dealing with another thirty-plus nations assembled at the table,” and was equally skeptical of the value of the Helsinki Commission.

When questioned whether the establishment of the Helsinki Commission was provocative, Fenwick maintained it was not.

In an interview with Meet the Press in 1977, Fenwick argued, “It is not our actions that are probing this sensitive thing. It is the fact that the government of the Soviet Union signed something saying to its citizens that they have the right to travel, that they have the right to reunification of families, that they have the right to information.”

Fenwick continued, “We must abide by the condition that the international organizations are living by.”

After its establishment, Rep. Fenwick became an original member of the Helsinki Commission and served as a commissioner until she retired from Congress. Her time in the House of Representatives continued to be impactful and courageous. She was lauded by the press for her diligence and ethics, classified by Walter Cronkite as “the conscience of Congress.” She remained a strong opponent of corruption and a driving advocate for human and civil rights throughout her tenure.

Rep. Fenwick set the tone for the continued commitment of the U.S. Congress to the Helsinki Final Act and established a base from which human rights could be prioritized in U.S. policy that is still in use today.