By Emma Derr,

Max Kampelman Fellow

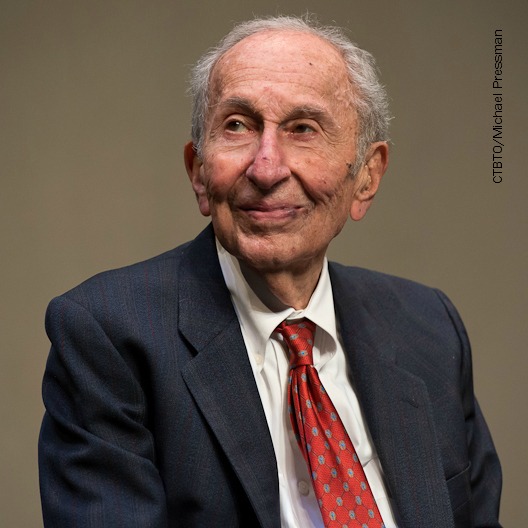

The Helsinki Commission’s flagship fellowship program recognizes former U.S. Ambassador Max Kampelman, who spent his life working toward comprehensive security at home and across the Atlantic.

Over his career, which spanned more than half a century, Kampelman defended the principles of the Helsinki Final Act, strengthened the Helsinki process, and fought to reduce—and later eliminate—nuclear arms. One of his strongest legacies was his belief in bipartisanship, demonstrated by his service to both Democrats and Republicans and in his role as a U.S. ambassador.

In the words of longtime Helsinki Commissioner Senator Ben Cardin (MD), “It was a privilege for me and so many of my colleagues to work with a great and good man, whose example reminded us every day: this is what leadership looks like.”

Max Kampelman: The Ambassador

Kampelman began his career as legislative counsel to Senator Hubert Humphrey before joining the private law practice of Fried Frank. Although he practiced private law for the majority of his career, Kampelman continued to serve the United States when called on by presidents of both parties.

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter asked Kampelman to represent the United States as the lead negotiator at the 1980 Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) meeting in Madrid, which sought to bring eastern European countries into compliance with the Helsinki Final Act.

The meeting was supposed to last two to three months. It lasted three years. Under President Ronald Reagan, Kampelman continued to lead these negotiations until an agreement was reached in 1983.

In 1990, in the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall, OSCE participating States gathered to unite their different definitions of European security. Kampelman led the U.S. delegation to this historic meeting and advocated for democratic elections and universal human rights.

“He played a pivotal role in securing agreement on the first international instrument to recognize the specific problem of anti-Semitism and the human rights problems faced by Roma,” said Sen. Cardin. “Moreover, at a moment when Europe stood at a crossroads, Max Kampelman negotiated standards on democracy and the rule of law that remain unmatched.”

“The Copenhagen document has been called by a number of professors of international law the most important international human rights document since the Magna Carta, and it spells out what a democracy means. If anybody was to come and join this process, they would be joining what is apparent, a series of ‘oughts;’ and that’s our task. Once the ‘oughts’ are there, we have a leg up toward the ‘is.’”

Amb. Max Kampelman in a 2003 interview

The Copenhagen document strengthened the Helsinki Process by including unprecedented provisions, such as the commitment to democracy as the only form of governance. It also emphasized the rights of national minorities and the right to freedom of association, freedom of conscience, and freedom of expression.

The CSCE eventually became today’s Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the world’s largest regional security organization.

Max Kampelman: The Arms Advisor

In addition to his work defending the Helsinki Final Act, Kampelman also negotiated arms control agreements and guided the United States through some of the most difficult periods of U.S.-Soviet relations.

By the end of his career, Kampelman had engaged in more than 400 hours of face-to-face negotiations with the Soviets.

He successfully protected the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), a system designed under Reagan to protect against potential nuclear attacks, from Soviet efforts to stifle it. He led negotiation efforts on the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty and the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), effectively reducing nuclear arms for the first time in history.

During the late phases of the Cold War, Kampelman helped arrange the release of political and religious dissidents from the Soviet Union.

“We cannot wish it away. It is here and it is militarily powerful. We share the same globe. We must try to find a formula under which we can live together in dignity. We must engage in that pursuit of peace without illusion but with persistence, regardless of provocation.”

Amb. Max Kampelman, ahead of 1985 arms negotiations

Kampelman dedicated much of his later years to Global Zero, envisioning a world without nuclear weapons and encouraging statesmen Henry Kissinger, Sam Nunn, William Perry, and George Shultz, to advocate for this goal.

For his service to his country, Kampelman received the Presidential Citizens Medal from President George H.W. Bush in 1989 and the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, from Bill Clinton in 1999.

Max Kampelman’s Early Life

Kampelman was born in New York in 1920 to parents who had immigrated from what was then part of Romania. He grew up in the Bronx and received a law degree from NYU in 1945.

During World War II, he registered for alternate service as a conscientious objector. Kampelman enrolled in a strict food and work regimen known as the Minnesota Starvation Experiment to help authorities understand how to treat prisoner of war and concentration camp survivors.

During this time, he finished his doctorate in political science from the University of Minnesota, titled “The Communist Party and the CIO: A Study in Power Politics.”

He opposed Communism and opposed war, but his feelings regarding nonviolence changed over time with the development of the atomic and hydrogen bombs, later leading him to renounce his earlier pacifist beliefs.

Kampelman said his prevailing desire for American foreign policy was to turn the 21st century into the century of democracy. He died on January 25, 2013, at age 92.