Mr. President, as Chairman of the Helsinki Commission, I am pleased to recognize the accomplishments of the Moscow Helsinki Group which will mark the thirtieth anniversary of its founding later this week in the Russian capital. I particularly want to acknowledge the tremendous courage of the men and women who, at great personal risk, established the group to hold the Soviet Government accountable for implementing the human rights commitment Moscow has signed onto in the historic Helsinki Final Act. Today, the Moscow Helsinki Group is the oldest human rights organization active in the Russian Federation. Having played a pivotal role in the struggle for human rights during the Soviet period, the group continues to work tirelessly for the cause of human rights, democracy and rule of law throughout Russia.

When, on behalf of the United States, President Ford signed the Helsinki Accords in August 1975, he was criticized in some circles for supposedly having accepted Soviet control and domination of Eastern Europe in return for what some viewed as worthless promises on human rights. Ultimately, the skeptics were proven wrong. The Helsinki Accords did not legitimize the Soviet conquest of Eastern Europe at the end of World War II. Moreover, by reprinting the entire text of the Accords in Pravda, the Soviet Government had publicly pledged to live up to certain human rights standards that were generally accepted in the West but only dreamed of in the Soviet Union and other Captive Nations. That fact would have huge consequences.

In late April 1976, Dr. Yuri Orlov, a Soviet physicist who had already been repressed for earlier advocacy for human rights, invited a small group of human rights activists to join in a public group committed to monitoring the implementation of the Helsinki Accords in the USSR. Others responded to this invitation and on May 12th, the creation of the Public Group to Assist the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords in the USSR was announced at a Moscow press conference organized by future Nobel Peace Prize winner Academician Andrei Sakharov. Among the founding members of the Moscow Helsinki Group, as it became known, were the current chairperson, Ludmilla Alexeyeva, Dr. Elena Bonner, who would endure prolonged persecution with Dr. Sakharov, her husband, and others like cyberneticist Anatoly (Natan) Sharansky. They were joined by seven brave and principled individuals who were ready to sacrifice their comfort, the professional lives, their freedom and even their lives on behalf of the cause of human rights in their homeland. More would join in subsequent days.

The Moscow Helsinki Group carried out its mission by collecting information and publishing reports on implementation of the Accords in various areas of human rights. The twenty-six documentation provided by the group proved particularly valuable when the signatories convened in Belgrade in 1977, to assess implementation of Helsinki provisions, including human rights.

Naturally, the Soviet Politburo and the Communist Party had no intention of tolerating citizens who actually expected their government to live up to the pledges it had signed in Helsinki. Some members of the Moscow Group were forced to emigrate; many were sentenced to long terms in labor camp, the Soviet “gulag,” while others were sent into internal exile far from families and loved ones. In September 1982, under the repressive rule of former KGB chief Yuri Andropov, the Moscow Helsinki Group was forced to suspend its activity. Only three members remained at liberty, and they were constantly harassed by the KGB. Tragically, founding member Anatoly Marchenko died during a hunger strike at Chistopol Prison in December 1986, only a few months before the Gorbachev government began to empty the labor camps of political and religious prisoners.

Between 1982 and 1987 it seemed that the Soviet Government had succeeded in driving the human rights movement abroad, to the labor camps of the gulag, or underground. The reality was that the Helsinki movement had brought to light the deplorable human rights situation in the Soviet Union and put the Kremlin on the defensive before a world increasingly sensitive to the fate of individuals denied their fundamental rights. The efforts by Helsinki activists in the USSR, together with a stiffened resolve of Western governments, helped bring the Cold War to end and bring down the barriers, both real and symbolic, that unnaturally divided Europe.

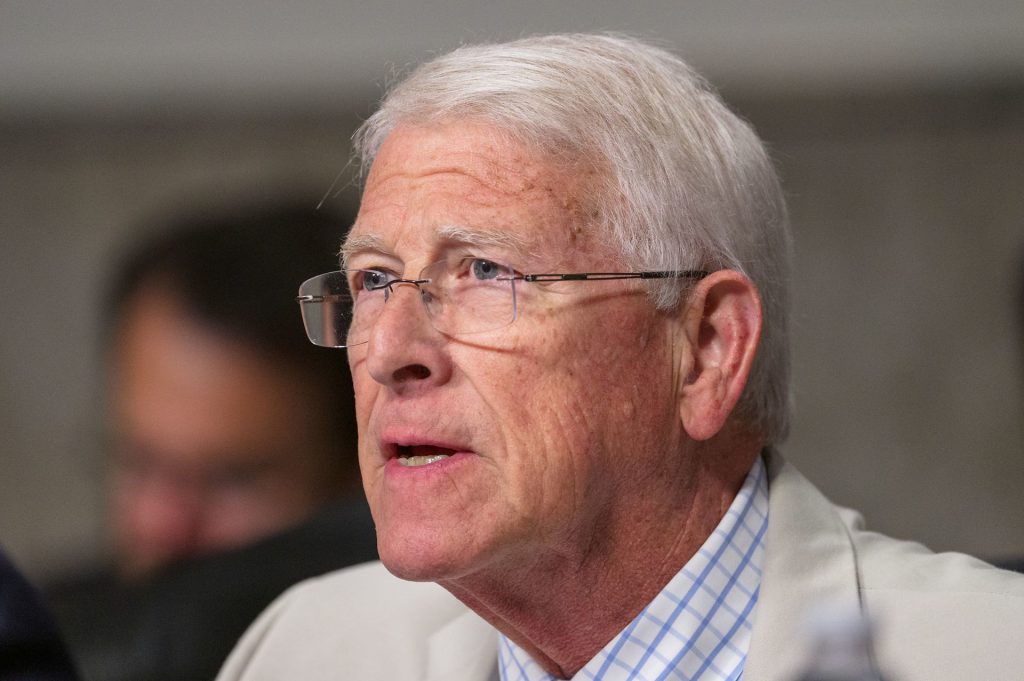

Reestablishment in July 1989, by several veteran human rights activists, the Moscow Helsinki Group faces new challenges in Putin’s Russia. I have met with Ludmilla Alexeyeva, a founding member who had been exiled to the United States during the Soviet era, who serves as the chairperson today. While Russia has thrown off so much of its Soviet past, the temptation of authoritarianism remains strong. Russia’s implementation of Helsinki commitments, particularly those concerning free and fair elections and democratic governance, remain of deep concern to me and my colleagues on the Helsinki Commission.

Ultimately, Mr. President, a strong and prosperous Russia will not be sustained by oil or natural gas revenues, but on respect for the dignity of its citizens and the observation of human rights, civil society and the rule of law. These goals remain at the heart of the Moscow Helsinki Group’s ongoing work. I salute the dedicated service of the members of the Moscow Helsinki Group, past and present, and wish them success in their noble endeavors to promote a free and democratic Russia.