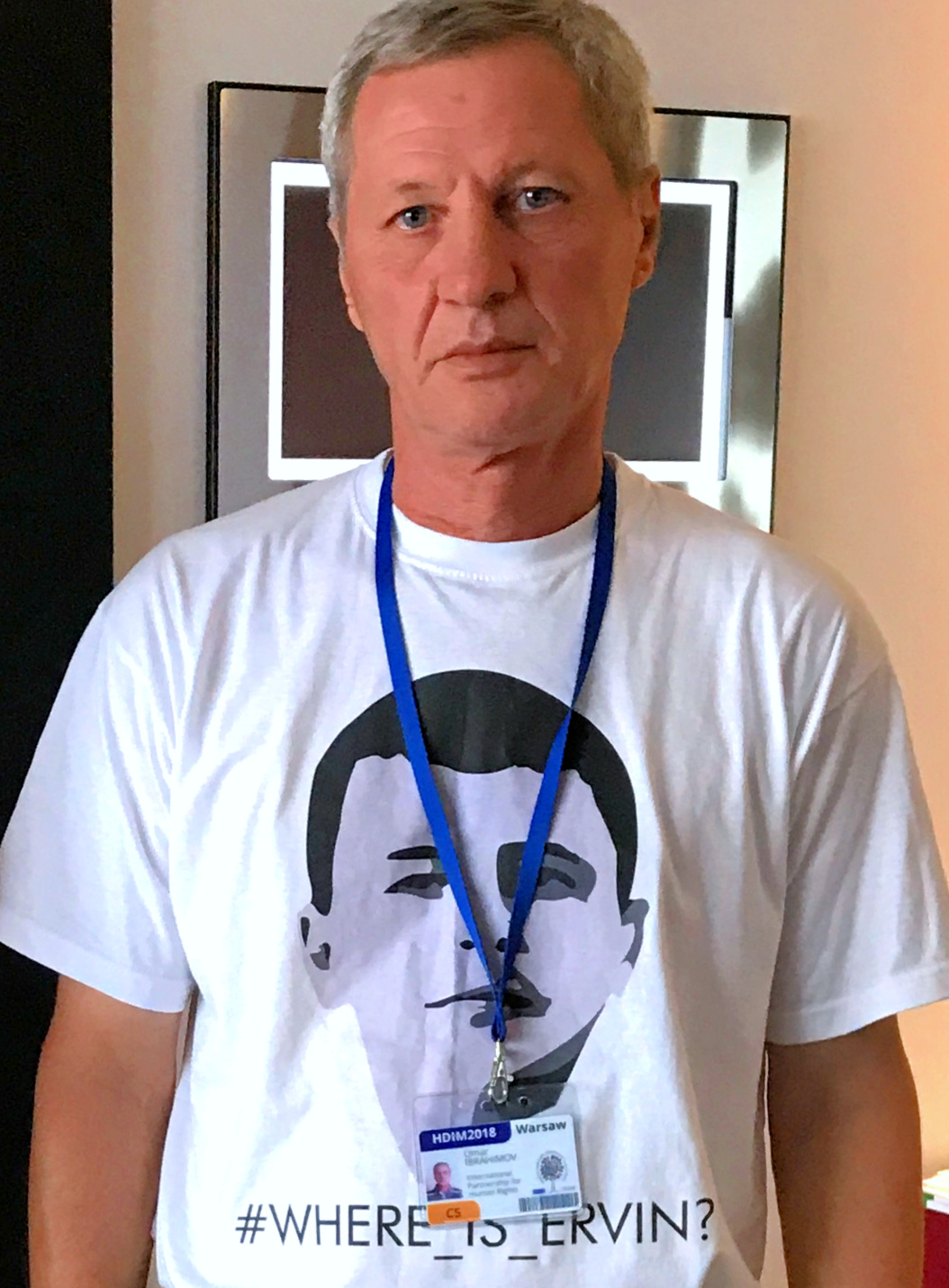

Umer Ibrahimov was one of the 750 civil society participants at the HDIM. He came to the HDIM to advocate on behalf of his missing son, Ervin Ibrahimov.

Ervin is one of many Crimeans who have disappeared since the Russian occupation of Crimea began in 2014. Crimean Tatar activists like Ervin have been particular targets of the Russian authorities, as have other residents of Crimea who refuse to accept Russian citizenship and integrate into the Russian-imposed social and political system.

Ervin disappeared in May 2016.

By Erika Schlager,

Counsel for International Law

From September 10 to September 21, 2018, approximately 1,500 representatives of governments and civil society from OSCE participating States met in Warsaw, Poland, for the annual Human Dimension Implementation Meeting (HDIM). The meeting was organized by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) under the leadership of its director, Ingibjörg Sólrún Gísladóttir.

The HDIM is the world’s largest regional human rights meeting and allows OSCE participating States and non-governmental representatives to take stock of countries’ implementation of OSCE human rights commitments. Each year, participants review the performance of participating States in areas including respecting fundamental freedoms of expression, assembly, association and religion or belief; safeguarding the rule of law, independence of the judiciary, and democratic elections; and countering racism, anti-Semitism and other forms of intolerance.

Each year also includes three subjects chosen for special focus. In 2018, those topics were freedom of the media; the rights of migrants; and combating racism, xenophobia, intolerance, and discrimination.

The meeting consists of opening and closing plenaries bracketing 18 working sessions. During the three-hour formal sessions, governmental and nongovernmental representatives speak on a first-come, first-served basis. At the end of each session, governments may make rights of reply.

Why Review Implementation?

When the Helsinki Final Act was signed in Finland in 1975, it enshrined among its ten Principles Guiding Relations between Participating States (the Decalogue) a commitment to “respect human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief, for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion” (Principle VII). In addition, the Final Act included a section on cooperation regarding humanitarian concerns, including transnational human contacts, information, culture and education.

The phrase “human dimension” describes the OSCE norms and activities related to fundamental freedoms, democracy (such as free elections, the rule of law, and independence of the judiciary), humanitarian concerns (such as trafficking in human beings and refugees), and concerns relating to tolerance and nondiscrimination (such as countering anti-Semitism and racism).

Signatories to the Helsinki Final Act agreed to systematically review the implementation of agreed commitments while considering the negotiation of new ones. Between 1975 and 1992, implementation review took place in the context of periodic “Follow-Up Meetings” as well as through smaller specialized meetings focused on specific subjects.

The OSCE participating States established permanent institutions in the early 1990s. In 1992, they agreed to hold periodic* Human Dimension Implementation Meetings to foster compliance with agreed-upon principles on democracy and human rights. Over time, a three-week annual review meeting in Warsaw was shortened to two weeks but augmented by three “Supplementary Human Dimension Meetings” in Vienna on subjects to be selected by the Chair-in-Office. The HDIMs are intended focus specifically on implementation review and are not intended as venues to draft or negotiate documents.

Strong participation by non-governmental organizations is one of the most notable features of the HDIM. OSCE modalities allow NGO representatives to raise issues of concern directly with government representatives, both by speaking during the formal working sessions of the HDIM and by organizing side events that examine specific issues in greater detail.

The United States has consistently advocated for the involvement of NGOs in the HDIM, recognizing the vital role that civil society plays in human rights and democracy-building initiatives. The United States has also supported webcasting the HDIM sessions. Videos of the plenaries and working session have been posted on the ODIHR Facebook page, and statements and other documents from the HDIM are available on ODIHR’s website.

A Draft Agenda

In 2018, for the first time, the HDIM was held without an agreed-by-consensus agenda tailored specifically to this meeting. According to past practice, preparation for each HDIM includes the adoption of three consensus decisions by the OSCE Permanent Council: first, a decision establishing the dates for the meeting; second, a decision selecting the three “specially selected topics” for in-depth focus; and third, a decision on the final meeting agenda.

Unfortunately, negotiations to adopt the HDIM agenda often drag on for months, impeding the ability of governments and NGOs to adequately prepare for the meeting. The Government of Russia is particularly adept at throwing up roadblocks designed to undermine the meeting without actually blocking it.

This year, Turkey added an additional complication. After walking out of the 2017 HDIM to protest the registration of an NGO it claimed was a “terrorist” organization due to its alleged connections to Fethullah Gülen, the Government of Turkey refused to agree to the 2018 HDIM agenda unless it was allowed to veto the participation of any NGO it disfavors.

Although there were no objections to the substance of the agenda, at the final Permanent Council meeting before the HDIM, Turkey blocked consensus over to the separate question of NGO access to the meeting.

As the HDIM is a standing meeting mandated by previous consensus decisions and Italy had already secured decisions setting the HDIM dates and special topics, the draft agenda was used as the basis for organizing this year’s HDIM.

NGO Participation

Earlier in 2018, responding in part to Turkey’s concerns, the OSCE Permanent Council established an informal working group to consider issues related to NGO participation in OSCE meetings.

Speaking rights for NGOs on an equal footing with governments has long been a hallmark of the HDIMs. Not surprisingly, some governments chafe at the participation of independent critical voices and have sought to curtail them in various ways. Uzbekistan, for example, denied an exit visa to former political prisoner and leading human rights defender Akazam Turgunov, preventing him from attending the 2018 HDIM. There were also reports in Tajikistan of pressure against civil society representatives to prevent them from participating in the HDIM as well as reprisals against family members of those who did participate.

2018 Highlights

Almost all OSCE participating States sent representatives to the 2018 HDIM. For the second year in a row, Turkey boycotted the meeting in the face of its inability to obtain the right to block the participation of NGOs to which Turkey objects. (San Marino was the only other participating State that did not attend.) The official delegations were joined by 750 nongovernmental representatives.

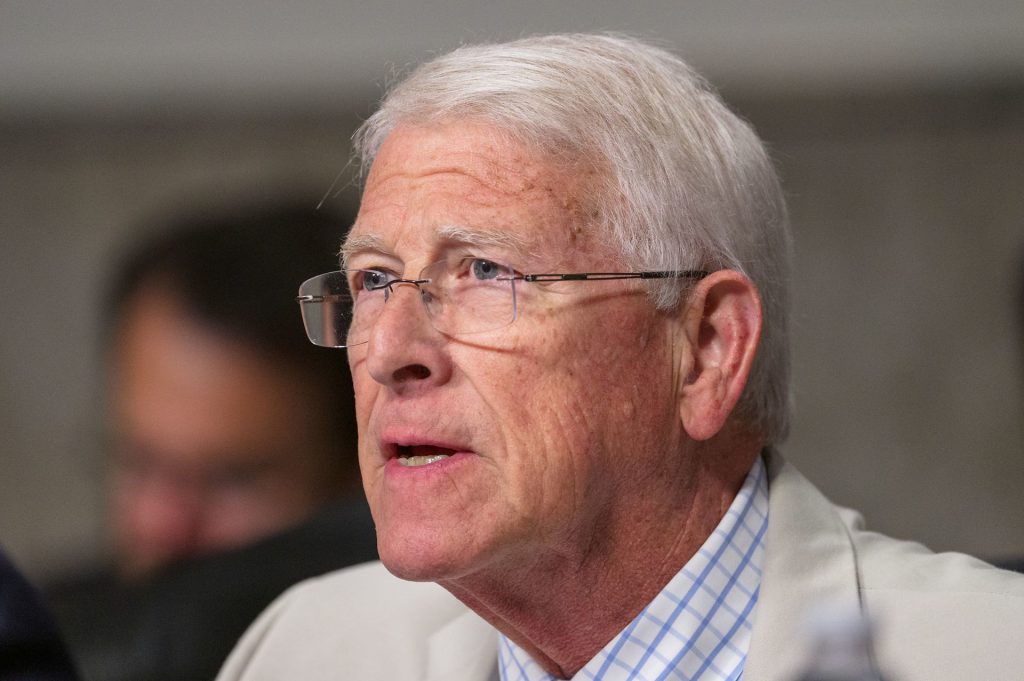

The U.S. delegation included Ambassador Michael G. Kozak, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, Head of Delegation; Ambassador Samuel D. Brownback, Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom; Michael J. Murphy, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs; Chargé d’Affaires Harry Kamian, U.S. Mission to the OSCE; Kristina Arriaga, Vice Chair, U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom; and Kyle Parker, Chief of Staff, U.S. Helsinki Commission.

U.S. statements focused heavily on Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, including abuses by Russia-led forces in the Donbas and occupation authorities in Crimea, as well as Russia’s serious human rights violations against its own population; the shrinking space for civil society and persecution of human rights defenders; and repressive measures against peaceful members of ethnic and religious groups, and hate crimes.

During the opening session, the United States noted that it had joined 14 other participating States on August 30 in invoking the OSCE’s Vienna Mechanism, requiring Russia to respond to reports of abuses by Chechen authorities against persons for their perceived or actual sexual orientation or gender identity, as well as against human rights defenders, lawyers, and members of independent media and civil society organizations. The Kremlin’s unwillingness to address these serious human rights violations has contributed to a climate of impunity for authorities in Chechnya.

The United States and other speakers also welcomed human rights improvements that have taken place in Uzbekistan over the past year and urged the government to continue sorely needed reforms.

As in past years, on the closing day the United States revisited the reasons that the Moscow Mechanism was invoked with Turkmenistan 15 years ago, noting the lack of adequate information on many individuals—including former OSCE Ambassador and Foreign Minister Batyr Berdiev and former Foreign Minister Boris Shikmuradov—who were arrested by authorities and subsequently disappeared in state custody,. This year, the U.S. statement was made jointly on behalf of Austria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

In connection with the HDIM, ODIHR held workshops with civil society focused on combatting trafficking in persons and on the special topic of racism, xenophobia, intolerance and discrimination with a focus on hate crimes.

There were approximately 100 other side events focused on specific countries or issues. Side events may be organized by governments, nongovernmental organizations, or international organizations. The United States also held bilateral meetings with government representatives and robust consultations with civil society.

Between the first and second weeks of the HDIM, 24 members of the U.S. delegation visited Auschwitz-Birkenau. January 27, 2019, will mark the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the death camp by Soviet forces in Nazi-occupied Poland.

*In exceptional years when the OSCE participating States hold a summit of heads of state or government, the annual review of human dimension commitments is included as part of a Review Conference which precedes the summit and also includes a review of the political-military and economic/environmental dimensions. The last OSCE Summit was in Astana, Kazakhstan, in 2010.