WASHINGTON—The Republic of Malta stepped up to take leadership of the world’s largest regional security organization—the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE)—demonstrating its commitment to uphold the principles of the organization, including on security, conflict resolution, democracy and human rights. Two years into Putin’s brutal, full-scale invasion of Ukraine, much of the OSCE’s focus continues to revolve around responses to the war, including using the organization to condemn Russian aggression and hold the government of the Russian Federation to account, to launch international investigations on Russian war crimes, and to reestablish an OSCE mission on the ground in Ukraine. The OSCE has remained at the forefront despite Russian efforts to block consensus and undermine the Organization and its work.

The OSCE also must address other challenges in the region, including spillover effects of Putin’s war in Ukraine, conflict resolution efforts in the Caucasus, and backsliding in some countries on human rights, democracy, and the rule of law. Antisemitic attacks and rhetoric have soared across the OSCE region, particularly following the October 7, 2023 Hamas attack on Israel that killed thousands. Combating human trafficking continues to be an important focus as millions of women and children who fled Ukraine are still vulnerable targets of traffickers. Attacks on independent media continue in some OSCE participating States, including Russia, Belarus and most recently, Kyrgyzstan.

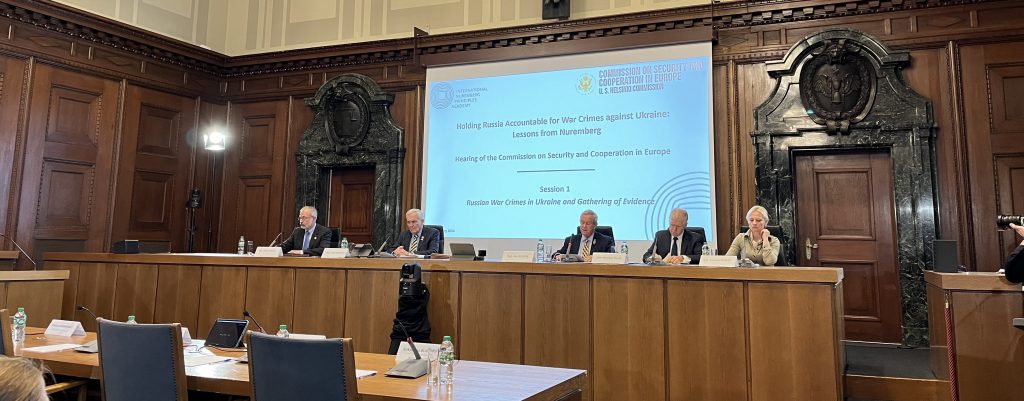

At this hearing, Malta’s Foreign Minister and OSCE Chairperson-in-Office Ian Borg will discuss Malta’s priorities in the OSCE and how it will address Russia’s war on Ukraine and other regional challenges.

All hearings are open to the public.